Linked Open Usable Data (LOUD)

The Semantic Web, with its use of Resource Description Framework (RDF) graphs, offers significant potential for data modelling and reasoning, but faces challenges in terms of query complexity, data handling, and visualisation. Despite these obstacles, the advent of JavaScript Object Notation for Linked Data (JSON-LD) represents a notable advance, providing a flexible data representation that addresses some of these issues by allowing dual treatment as both JSON and a graph.

Linked Open Data (LOD) has been pivotal in fostering a web of openly connected datasets. The progression to Linked Open Usable Data (LOUD) underscores an evolution towards making data not just accessible and linked but also readily usable for a broader audience, particularly software developers. This shift is propelled by the understanding that data’s real value is unlocked through its usage. LOUD aims to enhance scalability, both from technical perspectives and in terms of data production and adoption, making data more interconnected and thus more useful.

JavaScript Object Notation for Linked Data (JSON-LD)

JSON-LD is a modern web standard designed to simplify the encoding of linked data using the widely known JSON format. As a compact and easy-to-manage data format, JSON-LD enhances the ability to share structured data across disparate systems on the Web, while embedding rich semantic capabilities. It achieves this by allowing data to be serialised in a way that is compatible with traditional JSON, yet interpretable by RDF-based semantic processing tools.

At its core, JSON-LD introduces a context (@ context) that maps terms in a JSON document to Internationalised Resource Identifiers (IRIs) used in RDF vocabularies. This mapping allows JSON documents to be interpreted as RDF graphs, facilitating the integration of structured data into the Semantic Web without requiring developers to depart from familiar JSON syntax. The design of JSON-LD aims to bridge the gap between the ease of use of JSON and the rich data connectivity and interoperability offered by RDF. The development of JSON-LD was motivated by the need to make linked data more accessible to Web developers and to encourage wider adoption of Semantic Web technologies. By embedding semantic annotations directly into JSON, JSON-LD enables developers to contribute to the linked data cloud with a minimal learning curve, accelerating the growth of a semantically rich, interconnected web of data.

Per the JSON-LD 1.1. specification:

JSON-LD is a concrete RDF syntax as described in RDF11-CONCEPTS. Hence, a JSON-LD document is both an RDF document and a JSON document and correspondingly represents an instance of an RDF data model. However, JSON-LD also extends the RDF data model to optionally allow JSON-LD to serialize generalized RDF Datasets.

The strategic adoption of JSON-LD as a means to reconcile the simplicity of JSON with the descriptive power of RDF has sparked an insightful debate about its practical implications and its classification as a polyglot format. A blog post by Tess O’Connor outlines several challenges that emerge from this approach, including issues related to dual data models, algorithmic complexity, and the potential brittleness and performance impacts of JSON-LD’s @ context mechanism. To address these challenges, a strategic focus on simplicity and clarity is advocated. Adopting a straightforward JSON format that doesn’t require knowledge of RDF can simplify interactions and improve the appeal and usability of the data. In addition, creating canonical mappings from JSON to RDF addresses the needs of RDF users while maintaining the accessibility of the base format. In addition, the adoption of stable sets of @ context is critical for consistent data exchange.

However, this polyglot characterisation of JSON-LD has been met with counter-arguments, such as those from Pierre-Antoine Champin, that offer a different perspective. Critics argue that JSON-LD should not be considered a polyglot format in the strictest sense because it operates on a “JSON then JSON-LD” basis rather than an “either/or” scenario. In this view, any JSON-LD processor first interprets the document as JSON before applying the JSON-LD layer, similar to how other JSON formats, such as GeoJSON, encode specific types of information beyond the basic JSON structures. This process does not make these formats polyglots, but rather extensions of JSON that provide mappings to more complex data models, thus emphasising JSON-LD’s role in simplifying the transition to semantically enriched data on the web.

Building upon this understanding, the LOUD design principles emerge as guiding forces in the quest to make data not only accessible and interconnected but fundamentally usable and intuitive for developers and end-users alike.

LOUD Design Principles

One of the main purposes of LOUD is to make the data more easily accessible to software developers, who play a key role in interacting with the data and building software and services on top of it, and to some extent to academics. As such, striking a delicate balance between the dual imperatives of data completeness and accuracy, which depend on the underlying ontological construct, and the pragmatic considerations of scalability and usability, becomes imperative.

Similar to Tim-Berners Lee’s Five Star Open Data Deployment Scheme, Robert Sanderson listed five design principles that underpin LOUD:

- The right Abstraction for the audience

- Few Barriers to entry

- Comprehensible by introspection

- Documentation with working examples

- Few Exceptions, instead many consistent patterns

A. The right Abstraction for the audience

Developers do not need the same level of access to data as ontologists, in the same way that a driver does not need the same level of access to the inner workings of their car as a mechanic. Use cases and requirements should drive the interoperability layer between systems, not ontological purity.

B. Few Barriers to entry

It should be easy to get started with the data and build something. If it takes a long time to understand the model, ontology, sparql query syntax and so forth, then developers will look for easier targets. Conversely, if it is easy to start and incrementally improve, then more people will use the data.

C. Comprehensible by introspection

The data should be understandable to a large degree simply by looking at it, rather than requiring the developer to read the ontology and vocabularies. Using JSON-LD lets us to talk to the developer in their language, which they already understand.

D. Documentation with working examples

You can never intuit all of the rules for the data. Documentation clarifies the patterns that the developer can expect to encounter, such that they can implement robustly. Example use cases allow contextualization for when the pattern will be encountered, and working examples let you drop the data into the system to see if it implements that pattern correctly.

E. Few Exceptions, instead many consistent patterns

Every exception that you have in an API (and hence ontology) is another rule that the developer needs to learn in order to use the system. Every exception is jarring, and requires additional code to manage. While not everything is homogenous, a set of patterns that manage exceptions well is better than many custom fields.

LOUD Standards

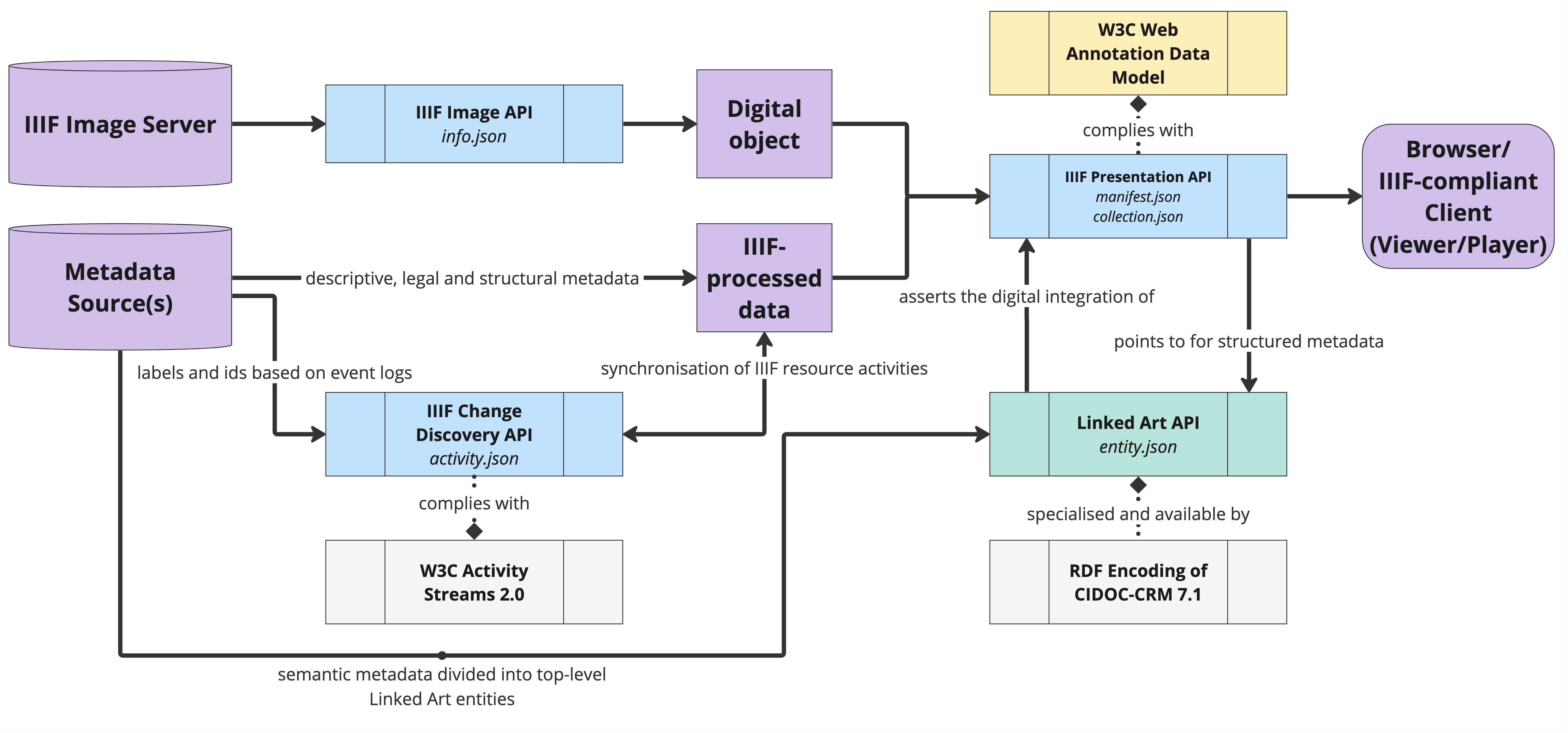

Systems embodying LOUD principles include the International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF), the Web Annotation Data Model, and Linked Art, demonstrating the ethos of making data more accessible, connected, and usable:

- International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF), especially the IIIF Presentation API 3.0 which describes how the structure and layout of a digital object can be made available in a standard manner, defining their appearance in viewers and players through the

Manifest, a JSON-LD file bundling all elements of a IIIF resource with essential metadata and structural information. - Web Annotation Data Model: It offers a standardised framework for creating annotations on web resources, promoting semantic data integration and use across the web.

- Linked Art: A community effort to define a metadata application profile and API for describing and interacting with cultural heritage resources.

IIIF and Linked Art are exemplary community-driven efforts, where ongoing engagement and collaboration within their respective communities ensure continuous development and updates. As for the Web Annotation Data Model, while it doesn’t operate as an active community, it remains a recognised LOUD standard. In the event that updates are needed, a dedicated World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) working group would probably be re-established or revamped.

IIIF

IIIF is both a model for presenting and annotating content as well as a global community that develops shared application programming interfaces (APIs), implements them in software, and exposes interoperable content.

IIIF was initially established in 2011 as a community-based initiative that emerged from the convergence of two pivotal endeavours. One strand of this narrative revolved around the imperative to facilitate the seamless exchange of high-definition images over the internet. This aspiration arose as a practical solution to mitigate the proliferation of duplicated images required for distinct projects. The desire to avoid the necessity of sending substantial volumes of image data via conventional methods, such as mailing terabytes of data on hard drives, led to the contemplation of a web-based approach for sharing images that could break down silos. The second strand, interwoven with the first, emanated from the explorations and experiments surrounding the interoperability of digitised medieval manuscripts. The DMSTech group at Stanford, operational from 2010 to 2013, provided the fertile ground for these reflections. These deliberations ultimately led to the development of the Shared Canvas Data Model, which remains a foundational influence on the IIIF Presentation API to this day.

As of August 2024, IIIF has introduced six specifications, with the Image and Presentation APIs being the most notable, both updated to version 3 in June 2020 and often considered the core IIIF APIs. Additionally, the Content Search and Authorization Flow APIs, both at version 2 and released in 2022 and 2023 respectively, are expected to receive updates to match the core APIs’ standards. The Change Discovery and Content State APIs, both in version 1.0, play essential roles in discovering, aggregating, and sharing IIIF resources.

The development of the IIIF specifications is firmly rooted in the IIIF design principles, which have influenced similar methodologies such as the LOUD design principles. These principles emphasise clear, practical goals aligned with shared use cases to meet the needs of developers effectively. By focusing on simplicity, minimal barriers to entry, and adherence to good web and Linked Data practices, these principles have been crucial in making the IIIF APIs both user-friendly and technically sound. They advocate for ease of implementation and internationalisation, promoting a flexible yet cohesive structure that naturally leads to usable and accessible data.

IIIF Image API

The IIIF Image API is a RESTful web service that allows users to interact with images in a highly flexible manner. It facilitates the retrieval of images via standard HTTPS requests, effectively serving as an agreement between an image client and an image server to deliver image pixels. This API defines its own URI syntax, enabling users to interact with images in two primary modes: image requests and image information requests.

In the image request mode, users can retrieve a specific image derived from the underlying content, with parameters that control the region, size, rotation, quality, and format of the returned image. This allows for advanced functionalities such as panning, deep zooming, and the sharing of specific regions of interest within an image. The image information request mode (info.json) provides details about the image service itself in JSON-LD, including the characteristics and available functionalities of the image service.

IIIF Presentation API

The IIIF Presentation API’s goal is to deliver structured and human-readable information about digital objects or collections, designed to drive remote viewing experiences. It is a JSON-LD-based framework for displaying minimal descriptive and legal metadata, focusing primarily on enhancing the user experience rather than providing semantic metadata for search engines. However, it does offer flexibility for IIIF adopters to incorporate structured metadata for discovery purposes through properties like rdfs:seeAlso.

Loosely based on the Shared Canvas Data Model, the Presentation API organises content into four main resource types: Collection, Manifest, Canvas, and Range. Each of these serves a distinct function within the API’s framework, enabling a rich and interactive presentation of digital objects. Additionally, the API integrates types defined by the Web Annotation Data Model, such as AnnotationCollection, AnnotationPage, Annotation, and Content, further enhancing its capacity to deliver detailed and structured digital content.

Compatible software

These APIs, central to the IIIF ecosystem, underscore the initiative’s commitment to interoperability, flexibility, and a user-centric approach in the handling and presentation of digital images and their associated metadata. The widespread adoption of these APIs by numerous institutions around the world highlights their robustness and utility.

The suite of IIIF-compliant software encompasses a diverse range of tools, each catering to specific aspects of the framework. Central to this suite are image servers, predominantly tailored to align with the IIIF Image API, such as IIPImage, Cantaloupe, or SIPI. Complementing these servers are image viewers, designed to be compatible with either the Image API alone, like OpenSeadragon (OSD) and Leaflet-IIIF, or with both of the core IIIF APIs. With the release of version 3.0 of the Presentation API, A/V players have also been developed, which frequently comply with the Image API as well. Examples of known clients that support the Image and Presentation APIs 3.0 are Mirador, the Universal Viewer (UV), Annona, Clover, and Ramp. As support and behaviour vary, a dedicated IIIF 3.0 Viewer Matrix was created.

The embedded viewer below is Mirador, a powerful IIIF-compliant client. Stanford University played a pivotal role in rebuilding it, marking a key milestone that exemplifies the spirit of community-driven effort within the IIIF initiative. This endeavour, which has since been placed in the hands of the community, was later augmented through a collaborative partnership with Harvard University Library. The cooperative dynamics and collective contributions fundamental to the success and advancement of IIIF are clearly reflected in the widespread adoption and continued development of Mirador.

Web Annotation Data Model

The Web Annotation Data Model is a W3C standard that provides an extensible and interoperable framework for creating and sharing annotations across various platforms. It defines relationships between resources using an RDF graph, which includes key components such as the annotation, a web resource, the body, and the target. This model allows a single comment to be associated with multiple resources, enhancing the semantic integration of data across the web. The Web Annotation Working Group, which was chartered from August 2014 to October 2016 and extended to February 2017, played a pivotal role in developing and officially vetting this specification as a standard.

Here is an example of machine-generated annotations in a IIIF setting. The JSON-LD snippet represents an AnnotationPage that contains one or more annotations related to a particular IIIF resource.

{

"@ context": "http://iiif.io/api/presentation/3/context.json",

"id": "https://iiif.participatory-archives.ch/annotations/SGV_12N_08589-p1-list.json",

"type": "AnnotationPage",

"items": [

{

"@ context": "http://www.w3.org/ns/anno.jsonld",

"id": "https://iiif.participatory-archives.ch/annotations/SGV_12N_08589-p1-list/annotation-436121.json",

"motivation": "commenting",

"type": "Annotation",

"body": [

{

"type": "TextualBody",

"value": "person",

"purpose": "commenting"

},

{

"type": "TextualBody",

"value": "Object Detection (vitrivr)",

"purpose": "tagging"

},

{

"type": "TextualBody",

"value": "<br><small>Detection score: 0.9574</small>",

"purpose": "commenting"

}

],

"target": {

"source": "https://iiif.participatory-archives.ch/SGV_12N_08589/canvas/p1",

"selector": {

"type": "FragmentSelector",

"conformsTo": "http://www.w3.org/TR/media-frags/",

"value": "xywh=319,2942,463,523"

},

"dcterms:isPartOf": {

"type": "Manifest",

"id": "https://iiif.participatory-archives.ch/SGV_12N_08589/manifest.json"

}

}

},

Body

The body of an annotation is where the content of the annotation is defined. In this example, there are three textual bodies:

- A “TextualBody” with the value “person” for

commenting. - Another “TextualBody” with the value “Object Detection (vitrivr)” for

tagging. - A third “TextualBody” with HTML content indicating a detection score, also for

commenting.

These bodies represent the content of the annotation, including comments and tags related to the annotated resource.

Target

The target specifies where the annotation applies. In this setting, it points to a specific area of a IIIF Canvas. Key details include:

- The source URL, identifying the specific Canvas within this IIIF Presentation API 3.0 resource.

- A selector of type “FragmentSelector”, using the Media Fragments specification (with a value indicating the specific rectangular area on the canvas targeted by the annotation).

- A link (

dcterms:isPartOf) to the IIIF Manifest that the Canvas is part of.

Linked Art

Linked Art is a community and a CIDOC (ICOM International Committee for Documentation) Working Group collaborating to define a metadata application profile for describing cultural heritage, and the technical means for conveniently interacting with it. It aims to solve problems from real data, is designed for usability and ease of implementation, which are prerequisites for sustainability. The Linked Art V1.0 specifications were released on 19 February 2025.

Linked Art presents a layered framework that distinguishes between the conceptual and implementation aspects. At its core, Linked Art is a data model or metadata application profile that draws extensively from the RDF implementation of version 7.1.3 of CIDOC-CRM. The Getty Vocabularies are leveraged as core sources of identity for domain-specific terminology. JSON-LD 1.1 is chosen as the preferred serialisation format, promoting clarity and interoperability. This framework constructs common patterns, integrating conceptual models, ontologies, and vocabulary terms. These elements are derived from real-world scenarios and contributions from the diverse participants and institutions within the Linked Art community.

| Level | Linked Art |

|---|---|

| Conceptual Model | CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model (CRM) |

| Ontology | RDF encoding of CRM 7.1, plus extensions |

| Vocabulary | Getty Vocabularies, mainly the Art & Architecture Thesaurus (AAT), as well as the Thesaurus of Geographic Names (TGN) and the Union List of Artist Names (ULAN) |

| Profile | Object-based cultural heritage (mainly art museum oriented) |

| API | JSON-LD 1.1, following representational state transfer (REST) and web patterns |

The Linked Art data model, in its domain-specific application, particularly resonates with five of these facets: “what,” “where,” “who,” “how,” and “when.”

Exploring the specifics of the Linked Art API, four key areas are highlighted: ease of implementation, consistency across representations, division of information, and URI requirements.

Linked Art prioritises ease of implementation, making it simple enough to deploy even with hand-crafted files, though automation is preferred for larger data volumes. A crucial aspect is ensuring consistency across representations, with each relationship contained within a single document to maintain clarity and coherence. The framework also emphasises the division of information, scaling from many to few - such as from a page to a book, and then to a collection - ensuring a clear hierarchy. The API’s identity and URI requirements are designed for simplicity. One-to-one relationships are embedded directly without needing separate URIs, making the data model more accessible. URIs for records are kept simple, with no internal structure, ensuring ease of use and navigation. This approach makes Linked Art an efficient tool for representing and managing cultural heritage data.

In Linked Art, the division of the graph avoids duplication of definitions across records. Full URIs are used for references, simplifying client processing. Embedded structures do not carry URIs, preventing unnecessary complexity. The Linked Art API currently features eleven endpoints, which align with the conceptual model:

- Concepts: Types, materials, languages, and others as full records rather than external references

- Digital Objects: Images, services, and other digital objects

- Events: Related activities that are not part of other entities

- Groups: Groups and organisations

- People: Individuals

- Physical Objects: Artworks, buildings, books, and other physical items

- Places: Geographic locations

- Provenance Activities: Events in the history of a physical item

- Sets: Collections and exhibition sets

- Textual Works: Distinct textual entities like book content or journal articles

- Visual Works: Image content like paintings or drawings

Each endpoint is supported by detailed documentation, including the required and permitted patterns, along with a corresponding JSON schema.

LOUD Ecosystem

These three systems are complementary and can be used either separately or in conjunction.

A LOUD ecosystem is characterised by an emphasis on interoperability between independently developed systems. This approach to design and implementation promotes semantic interoperability, ensuring that data can be understood and used across platforms and applications without the need for centralised coordination. By adhering to the LOUD principles, systems can communicate more effectively and share data in a way that is meaningful and useful to a wide range of users. This level of interoperability supports the creation of a more integrated and accessible digital environment, where data from different sources can be seamlessly connected and used for a variety of purposes.